Surviving the Annapurna Circuit

Note: This is the start of the Annapurna travelogue, which is in 4 parts.

I’m a mountain person. Wasn’t raised that way, don’t always want to be one (like when I am not amongst them), the more rugged the better, I even like the pain that goes with the beauty. In early 2004 I had just spent 3 months on small islands in Indonesia and Malaysia, and many more cumulative months over the last two years living on the best in Thailand, but Nepal was the first place that really felt like home. Don’t get me wrong, I love beaches - I was raised on seafood and Pawley’s Island – but there is only so much I can do on them… collect shells, dive with sea turtles, explore reefs, walk the beaches, swim for exercise, soak up beer and sun, explore the interior jungles, and so on. I was beached out (what a luxury, to be able to do something you love until you are sick of it, then move on to something else you love!) and Nepal was the cure. It had actually been years since I had set foot midst peaks – the Sierras of California and somewhere in the distant past (China will do that to you – everything before seems remote) all those years in Idaho (and Utah, and Wyoming, and Montana…) and my heart soared. You can’t actually

see the mountains from Kathmandu – the valley is just too polluted – but everywhere there was the promise; I was staying in the primitive Durbar Square area but the popular Thamel district was thick beyond belief with all the trappings of a modern alpinist environment. Guide services, trekking companies, outdoor gear rental and retail stores, expedition stuff, and gorgeous posters are everywhere. And the city itself was so exotic that I almost didn’t want to leave – my neighborhood of muddy

see the mountains from Kathmandu – the valley is just too polluted – but everywhere there was the promise; I was staying in the primitive Durbar Square area but the popular Thamel district was thick beyond belief with all the trappings of a modern alpinist environment. Guide services, trekking companies, outdoor gear rental and retail stores, expedition stuff, and gorgeous posters are everywhere. And the city itself was so exotic that I almost didn’t want to leave – my neighborhood of muddy  alleys and funky smells had been continuously inhabited for over a thousand years and it felt every minute of it. Neighborhoods that looked like they had never seen a foreigner, whispers of “hashish!” (its the best in the world, and you get a free colorful cultural experience in a back alley with your purchase), street urchins just begging to be paid attention to, throngs surrounding sacred architectural edifices, rickshaws and the press of sweaty flesh – it was everything I wanted it to be and more. But you only get 2 months in the country and it was time to feel the trail underneath my feet – I advertised for partners on the local bulletin boards, found a likely Yank and Aussie with similar interests, we hired a local guide Raj (just in case), bought and rented what we might need for at least 3 weeks away from civilization, boarded the bus with its load of goats and produce,

alleys and funky smells had been continuously inhabited for over a thousand years and it felt every minute of it. Neighborhoods that looked like they had never seen a foreigner, whispers of “hashish!” (its the best in the world, and you get a free colorful cultural experience in a back alley with your purchase), street urchins just begging to be paid attention to, throngs surrounding sacred architectural edifices, rickshaws and the press of sweaty flesh – it was everything I wanted it to be and more. But you only get 2 months in the country and it was time to feel the trail underneath my feet – I advertised for partners on the local bulletin boards, found a likely Yank and Aussie with similar interests, we hired a local guide Raj (just in case), bought and rented what we might need for at least 3 weeks away from civilization, boarded the bus with its load of goats and produce,  and were on our way to Besisahar – trekking has increased in popularity and convenience since the heyday of the 60’s, but it is still essentially unchanged; Nepal’s Himalayas can only be accessed on foot, and everything about the experience is still pretty rough. We were there in the off season and the tourists were pretty thin – just the way I like to travel.

and were on our way to Besisahar – trekking has increased in popularity and convenience since the heyday of the 60’s, but it is still essentially unchanged; Nepal’s Himalayas can only be accessed on foot, and everything about the experience is still pretty rough. We were there in the off season and the tourists were pretty thin – just the way I like to travel. Even with the long rickety bus ride (with goats on board!), you still end up at a frontier end-of-the-road town that is in the distant lowlands, just a dusty place to lace your boots one more time and hope you haven’t forgotten anything important. Just start walking. Even though you start amidst tropical heat, rice fields and bananas (elevation 700 m) you learn quickly what Nepal trekking is all about – the track is a few foot wide dirt highway that is the only access to the outside world, and it is plied by the entire population (and their donkeys, and goats, and everything else) as they move goods and services throughout the region. In flip flops. It constitutes the main drag of every single village along the way, lending a view into the intimate lives of the residents, as they worked, played, ate, and slept. This part of Nepal (the Annapurna region) is not quite Third World – we were surprised to see fragile electrical transmission lines stretching along

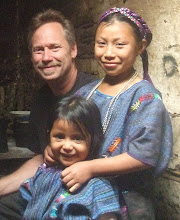

Even with the long rickety bus ride (with goats on board!), you still end up at a frontier end-of-the-road town that is in the distant lowlands, just a dusty place to lace your boots one more time and hope you haven’t forgotten anything important. Just start walking. Even though you start amidst tropical heat, rice fields and bananas (elevation 700 m) you learn quickly what Nepal trekking is all about – the track is a few foot wide dirt highway that is the only access to the outside world, and it is plied by the entire population (and their donkeys, and goats, and everything else) as they move goods and services throughout the region. In flip flops. It constitutes the main drag of every single village along the way, lending a view into the intimate lives of the residents, as they worked, played, ate, and slept. This part of Nepal (the Annapurna region) is not quite Third World – we were surprised to see fragile electrical transmission lines stretching along  most of our route (regularly spoiling our photographs – which are not allowed to include them as we try to capture the “real” Nepal) – it just happens to be a place where there are absolutely no roads and not even any sign of the wheel (motorcycles, bicycles, and even carts and wheel barrows were nowhere to be seen, only the very occasional handhewn water wheel, driving a prayer wheel or a grist mill). The joy of being so easily immersed in such an exotic culture – dark eyes, pierced noses, reverently religious Buddhist people, living like our distant ancestors did – was almost too much for me and I had a hard time keeping up with my mates; at each village I wanted to stop and spent the rest of my life, playing with the children and quietly contemplating my navel. But Rich (the Aussie firefighter – fit, built like a brick shit house, and a real social animal) - gobbled up the trail and it was a challenge not to be lost in his dust. This trek nominally takes 21 days

most of our route (regularly spoiling our photographs – which are not allowed to include them as we try to capture the “real” Nepal) – it just happens to be a place where there are absolutely no roads and not even any sign of the wheel (motorcycles, bicycles, and even carts and wheel barrows were nowhere to be seen, only the very occasional handhewn water wheel, driving a prayer wheel or a grist mill). The joy of being so easily immersed in such an exotic culture – dark eyes, pierced noses, reverently religious Buddhist people, living like our distant ancestors did – was almost too much for me and I had a hard time keeping up with my mates; at each village I wanted to stop and spent the rest of my life, playing with the children and quietly contemplating my navel. But Rich (the Aussie firefighter – fit, built like a brick shit house, and a real social animal) - gobbled up the trail and it was a challenge not to be lost in his dust. This trek nominally takes 21 days  and you have to keep moving to meet this target (and we intended to, for various reasons), though we would try to stay in the more unconventional villages along the way to make our journey seem more authentic. But years of being away from the trail took their toll – lazy beach life did not leave me as fit as I would have liked – and the pace occasionally seemed brutal. Luckily (?) we all soon had amoebic dysentery despite being careful with the water, so at least one of us had to pause for a toilet break every 50 meters.

and you have to keep moving to meet this target (and we intended to, for various reasons), though we would try to stay in the more unconventional villages along the way to make our journey seem more authentic. But years of being away from the trail took their toll – lazy beach life did not leave me as fit as I would have liked – and the pace occasionally seemed brutal. Luckily (?) we all soon had amoebic dysentery despite being careful with the water, so at least one of us had to pause for a toilet break every 50 meters. So we couldn’t travel but so far a day.

So we couldn’t travel but so far a day.Each little village has 2-3 little inns where you can stay, with tiny threadbare rooms (mattress/bed and candle) for <$2/night. Its firm tradition that the room is

cheap, even free, and you are mostly obligated to spend your food dollars where you sleep – dinner never had meat and was usually some choices of noodle or potato dishes or the local dal baht (literally “lentils and rice”, but you

cheap, even free, and you are mostly obligated to spend your food dollars where you sleep – dinner never had meat and was usually some choices of noodle or potato dishes or the local dal baht (literally “lentils and rice”, but you  never actually got the lentils, just their juice – you are supposed to eat this bland thing with your hands, and Raj and all the locals ate only this dish); other

never actually got the lentils, just their juice – you are supposed to eat this bland thing with your hands, and Raj and all the locals ate only this dish); otherlocal food was somewhat rare, but you could sometimes find thukpa or tintuk occasionally. Meat was obviously around on the hoof (chickens in cages, goats roaming across huge landscapes, and the occasional cow like thing) but never available. Places would seem to advertise yak meat, but it was only offered for one month of the year. A VERY good day included potato pancakes with yak butter and yak cheese; but where was all the flesh, bones, skins, etc. of the animals we saw? As we got higher and higher, we eventually found big bands of cashmere goats roaming across the open plain countryside (and giving birth! – the mother would drop the kid and fall behind the moving herd, then catch up a few hours later when the baby was up

to speed.), and at the very top – for only a day or so – wild blue sheep and yaks

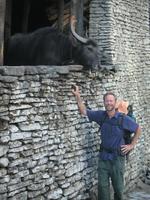

to speed.), and at the very top – for only a day or so – wild blue sheep and yaks  wandering on the steep hillsides; at one tiny hamlet I heard there were day old yak twins so I tracked them down and helped the shepards bring in the herd for the night, yelling and howling across the rugged landscape, below 25,000 foot peaks. By now it was just cold and deserted (in the rain shadow of the big peaks),

wandering on the steep hillsides; at one tiny hamlet I heard there were day old yak twins so I tracked them down and helped the shepards bring in the herd for the night, yelling and howling across the rugged landscape, below 25,000 foot peaks. By now it was just cold and deserted (in the rain shadow of the big peaks), too high for people to make a living at except for the occasional tea house or inn, and inside those we clustered together at night (Singaporeans, Bulgarians, Ukrainians, Israeli, British, etc. all now just citizens of the world) at the tables with charcoal fires placed below them, talking about how hard Thorung La (the big pass, at 5400 m - 17,769 feet) would be and who might not be able to make it. We had already lost Matt (much later I found him in Berkeley) at the tiny airstrip at Humdee, suffering so much from dysentery, altitude sickness, and

too high for people to make a living at except for the occasional tea house or inn, and inside those we clustered together at night (Singaporeans, Bulgarians, Ukrainians, Israeli, British, etc. all now just citizens of the world) at the tables with charcoal fires placed below them, talking about how hard Thorung La (the big pass, at 5400 m - 17,769 feet) would be and who might not be able to make it. We had already lost Matt (much later I found him in Berkeley) at the tiny airstrip at Humdee, suffering so much from dysentery, altitude sickness, and  knee pain that he decided to fly back out, and we were worried about some of the loose group of travelers that we had become used to sleeping and eating with over the week – one would need a horse and one would take several tries to get over, but everyone actually made it. It was solid snow and ice for the half day to the top, and surprisingly there was a tea shop at the very top, where you could get some small reward for the effort.

knee pain that he decided to fly back out, and we were worried about some of the loose group of travelers that we had become used to sleeping and eating with over the week – one would need a horse and one would take several tries to get over, but everyone actually made it. It was solid snow and ice for the half day to the top, and surprisingly there was a tea shop at the very top, where you could get some small reward for the effort.Next: painful all the way down, beautiful new country, a glimpse of Mustang...